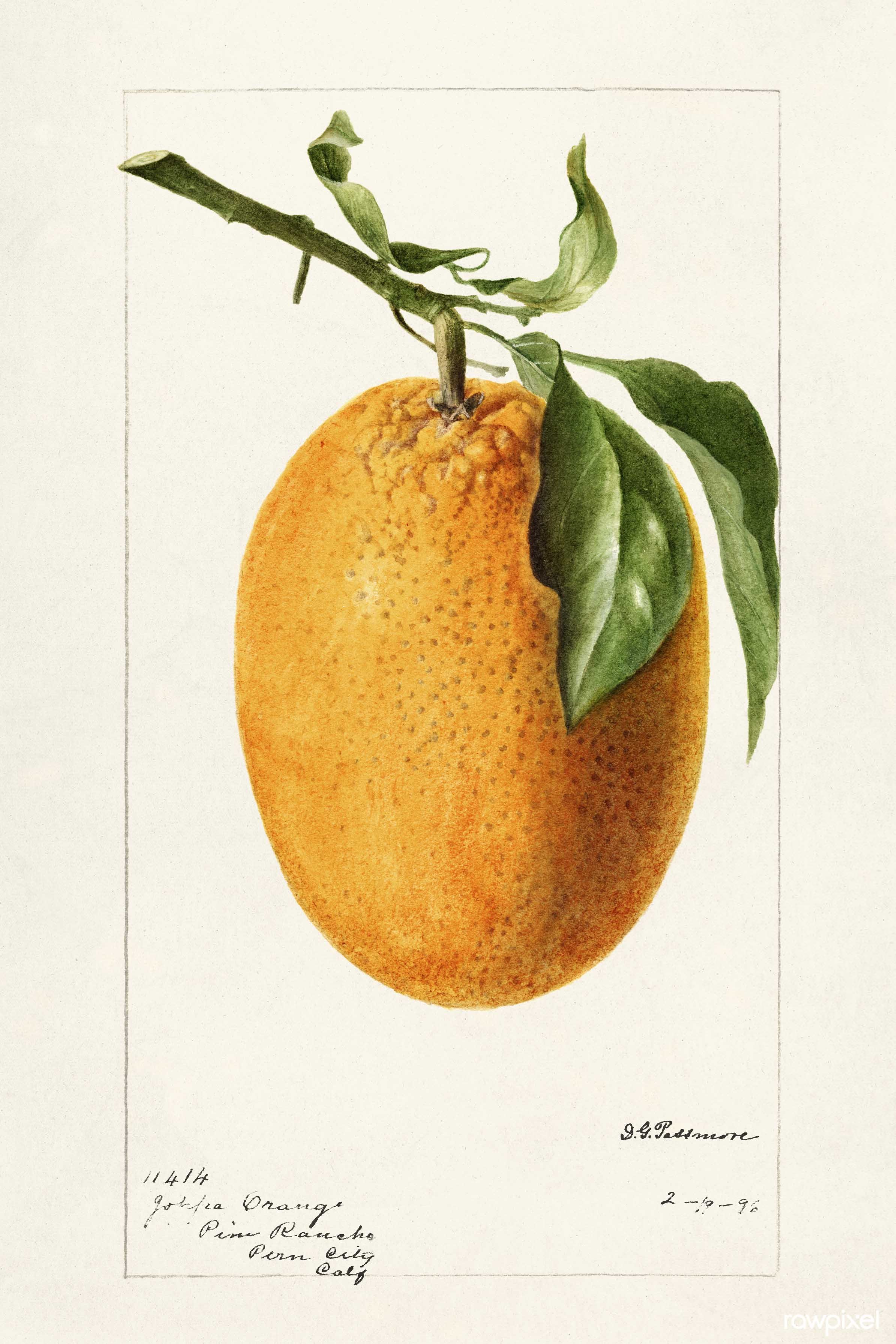

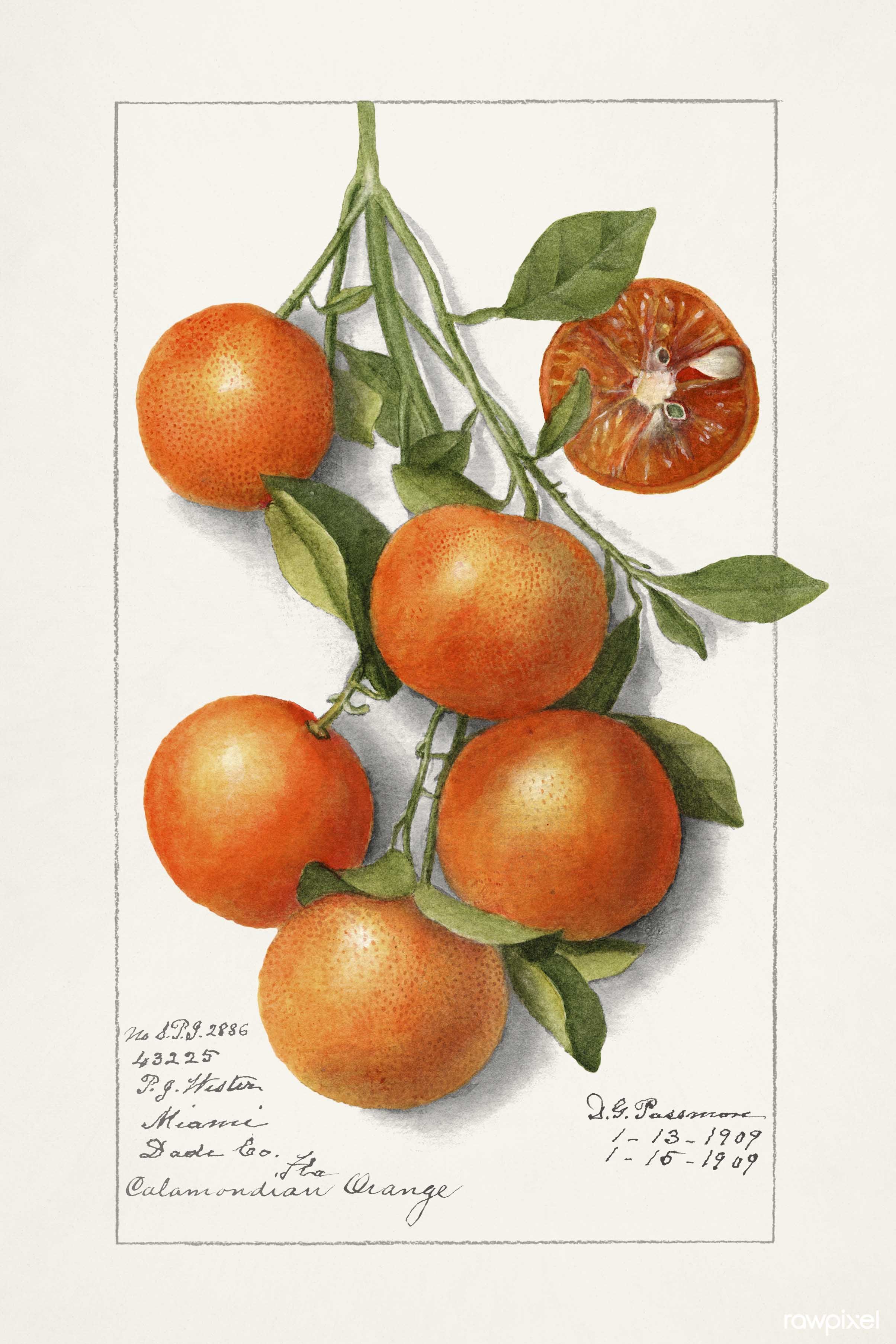

ILLUSTRATOR DEBORAH GRISCOM PASSMORE

Mangosteens (Garcinia Mangostana) (1909) by Deborah Griscom Passmore.

Original from U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection

The past few years have brought the profiles of government agencies and the people who work in them to an all-time high and perhaps at odds with popular imaginings, a number of artists have found themselves in the ranks with bureaucrats and scientists. One of these artists was Deborah Griscom Passmore, an accomplished illustrator who came to lead the USDA’s staff of artists in the Department of Pomology.

Deborah Griscom Passmore

Born on the 17th of July in 1840, to a family with slightly complicated naming traditions, she received the name “Deborah Griscom” after her paternal grandmother, a first cousin of Elizabeth “Betsy” Griscom Ross. Her mother Elizabeth K. Knight was a Quaker preacher and her father Everett Griscom Passmore was a farmer in Pennsylvania’s rural Edgmont Township.

The youngest of five children, Passmore was generally described as sensitive and was only five when her mother died of typhoid fever. Mary, one of the older siblings, left her own career plans to take care of the family and help Deborah finish basic schooling. Once she was old enough, Deborah attended the Weston Boarding School, where her mother had worked as a teacher prior to getting married.

After finishing boarding school, Passmore went on to study art at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. Established in 1848 by Sarah Peter, an Ohio native married to a British consul, the school was intended to provide women with trades instruction so that they could have a means of supporting themselves. An early director of the school, Emily Sartain, instituted life-drawing classes alongside the ones in lithography, woodcarving, and design. The inclusion of life-drawing classes was extraordinarily unusual for women’s art instruction at the time, but the thoroughness of the education lent greatly to the School of Design’s reputation and the school would go on to graduate a number of highly acclaimed female artists.

Passmore moved on to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art where her instructors included artists like Thomas Moran and then went to Europe to top off her education with tours of the Royal Galleries. She spent a year studying art in Europe and found particular inspiration in the botanical illustrations of Marianne North, a preeminent explorer known for her exceptionally precise illustrations.

Upon returning to the United States, Passmore dived into illustrations of wildflowers, lilies, and cacti, which she hoped to have published. Interestingly, this passion for floral illustration was one that was shared with her similarly named cousin Deborah Passmore Gillingham, who was a highly talented amateur artist. While none of these watercolors were ever published before her death, botanists like Edward Lee Greene respected her work greatly, remarking that “he did not know [flowers] could be painted with perfection.”

Watercolor painting by Deborah Griscom Passmore

Passmore spent some time as an art teacher in Philadelphia before moving to D.C. on the advice of William Wilson Corcoran, a banker whose love of art led him to found the United States’ first fine art gallery. Corcoran’s glowing endorsements were meant to pave a path for Passmore’s employment, but he died before she could establish herself in D.C. and she wound up taking a job at the USDA where she would come to establish a reputation as one of the nation’s foremost scientific illustrators, producing more than 1,500 pomology watercolors—one-fifth of the USDA’s collection.

Passmore was part of a wave of artists the USDA hired between 1886 and 1942 that would go on to produce more than 7500 paintings, drawings, and prints. At the turn of the 19th century, there were new varieties of fruit being cultivated in the United States at a record pace and there were hosts of discoveries of cultivars happening around the world. It was important for academia and America’s agricultural industry to find ways to disseminate new information. Photography wasn’t viable because it lacked color, whereas scientific illustration was an ideal solution.

Women like Ellen Isham Schutt, Elsie Lower Pomeroy, Amanda Almira Newton (eventually the country’s first Commissioner of Agriculture), and Deborah Griscom Passmore herself, played a prominent role at the USDA. While art education had become more available to women, the profession was still not a hospitable place and female artists frequently found themselves pigeonholed. The USDA, and scientific illustration more broadly, was a place where women were not as constrained to stereotypically feminine subjects—stomach-churning portraits of infected and mold covered fruit made up a not insignificant part of its oeuvre.

Unencumbered by societal expectations, Passmore’s talent in wildlife painting could be seen for what it was. Soon after Passmore was hired, she was tasked with creating the USDA exhibits for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago and she eventually rose to become the department’s head of illustration. Somewhat ironically, the fact that she never became a gallery artist is what may have saved her from obscurity; her scientific watercolors are not only ubiquitous as décor but also heavily referenced by taxonomists and historians.

Deborah Griscom Passmore’s life reflected not only how the artistic profession was changing for women, but also broader social changes that made it more feasible for women to opt to live alone or devote their lives to intellectual pursuits. Despite being well-liked in her circle, Passmore herself opted out of marriage, instead making a home with her cats Buttercup and Dandy Jim and choosing to teach art until her passing in 1911.

The USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection is available online and as a book entitled An Illustrated Catalog of American Fruits & Nuts.